Melanie Dickie, Mihai Covaser and Samantha Krieg are UBCO’s top award winners.

It’s graduation at UBC Okanagan and students are being celebrated by faculty, staff and their families.

With the pomp and circumstance, the piper, the proud families, celebrations and packed audiences, come a number of awards presented to students and faculty during the two days. For the students, the awards are based on academic merit—simply being the best they can be.

Governor General Gold Medal for Academic Excellence

A chance encounter at a conference with Associate Professor Adam Ford brought Dr. Melanie Dickie to UBC Okanagan, continuing on a path that would eventually be a gold medal journey.

“It was a bit of serendipity, a bit of curiosity and a lot of shared values when I first met Dr. Ford in 2019. It was one of those classic hallway conversations—brief but energizing—where you realize someone else is thinking about the same big questions you are. We were both interested in how science can move the needle in real-world decision making.”

Dr. Dickie, who received her doctorate in biology after conducting years of research with UBCO’s Wildlife Restoration Ecology Lab, is UBCO’s 2025 winner of the Governor General Gold Medal for Academic Excellence. The gold medal is awarded annually to the student with the highest academic standing graduating from a master’s or doctoral program.

Originally working with the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, Dr. Dickie had become familiar with Dr. Ford’s work through social media, where their professional interests overlapped in land use, conservation policy and the role of Indigenous leadership in ecological stewardship.

But after that chance conversation, she made the leap to UBCO to tackle “applied, gritty, make-a-difference kind of science.”

“It wasn’t just that the research fit, it was that the lab culture encouraged asking hard questions, working collaboratively and staying rooted in real-world effects,” she adds. “My time at UBCO has been transformational. Working with Dr. Ford and the lab has sharpened my thinking, expanded my skill set and pushed me to a new level as a researcher. It’s been one of those rare experiences where my gut feeling that something is ‘the right fit’ actually turns out to be true.”

Dr. Dickie, who was named a UBCO researcher of the year in 2023, is now back at the monitoring institute but has fond memories—including making Taylor Swift friendship bracelets with fellow researchers while camping—of hard work, driven research, lengthy Zoom calls and lasting friendships that add to the special honour of earning the gold medal. Her ongoing research will continue to cross paths with the Wildlife Restoration Ecology Lab and she will remain connected to the team.

“My time at UBCO helped me grow, and that’s changed how I approach my work—and how our team works together. I’m excited to be continuing to collaborate with Dr. Ford. We’re still focused on what first brought us together: using strong ecological theory to inform applied research that directly supports transparent, data-driven decisions—especially in landscapes where people and wildlife intersect every day.”

Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Inclusion, Democracy and Reconciliation

For many, Mihai Covaser is a prime example of the value of always putting the emphasis on what we can do, rather than what we cannot do.

Covaser, who graduated from UBCO yesterday with a Bachelor of Arts double major in Philosophy, Political Science and Economics, and French, is a top student and recognized leader in BC and Canada. Born in Bucharest, his family moved to Canada when he was young, eventually relocating to West Kelowna. Covaser graduated from Kelowna Secondary School in 2021 as class valedictorian with a dual dogwood diploma in French immersion.

When it came time for post-secondary studies, Covaser’s community involvement and career goals encouraged him to stay in the Okanagan.

“I chose UBCO in part to stay in my hometown and continue my community work, but I was also attracted to the philosophy, political science and economics program,” he explains. “It’s unique in its interdisciplinary approach and seemed perfectly situated to prepare me for my career goals in law.”

It’s also where Covaser continued to thrive. When he graduated yesterday, he was presented with the Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for Inclusion, Democracy and Reconciliation. The medal is offered annually to a graduating student who demonstrates academic merit and contribution to the life of the university and their community.

While at UBCO, Covaser created the Help Teach podcast, which he continues to produce and host, and worked as a language and writing tutor as well as a student ambassador. In addition, Covaser is an ambassador and director at the Rick Hansen Foundation—planning events that highlight accessibility and inclusion and guiding the organization—while also playing in a band and getting exceedingly high grades.

Not only is Covaser UBCO’s 2025 winner of a Lieutenant Governor’s medal, but he is also the recipient of the $10,000 Pushor Mitchell LLP Gold Leadership Prize. Available to graduating students in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Arts and Science and Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science, this donor-funded award recognizes students who have excelled academically and shown leadership while completing their degrees.

The award will come in handy when he moves to McGill University to begin the bilingual Bachelor of Civil Law and Juris Doctor program, where he will earn two degrees upon completion; the first degree in common law, the other in civil law.

“I have gained a deep curiosity for constitutional law and legal theory throughout my undergraduate studies,” he says. “While I haven’t chosen a specific field of law yet, I’m most interested in constitutional law and government work, entertainment law, human rights law and the functioning of the Canadian judiciary.”

Along with the medal and Pushor Mitchell recognition, he has also been presented with the Walley Lightbody Award in Law, the Amal Alhuwayshil Award in Campus Engagement and Leadership as well as the Petraroia Langford LLP Award in Legal Studies. He also received the University of British Columbia Okanagan Medal in Arts, which is awarded to the head of the graduating class with a BA degree.

Dr. Gordon Springate Sr. Award in Engineering

There was a time in her life when Samantha Krieg, who struggled in high school, didn’t think the world of academia was in the cards.

Now, the newly minted civil engineering graduate is not only one of UBCO’s top award winners, but she’s about to embark on her doctoral studies in structural engineering at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand.

“After researching countless career paths, everything from interior design to urban planning to food science, I landed on engineering,” she says. “What made me fall in love with it is finding creative solutions to real-world problems to help people and the environment.”

Krieg transferred to UBCO from Montreal’s Concordia University four years ago. Coming from a university of more than 40,000 students, Krieg appreciated UBCO’s smaller class sizes, and this helped her find opportunities for engagement in extracurricular activities and undergraduate research.

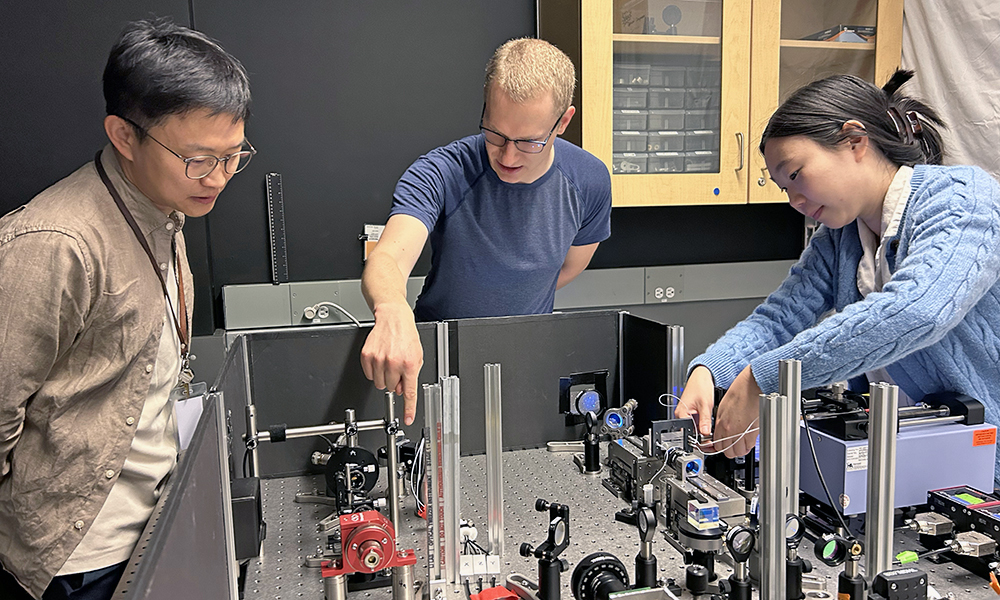

Part of this undergraduate research included work in Dr. Lisa Tobber’s Advanced Structural Simulation and Experimental Testing Group—a team that focuses on the social, environmental and economic factors behind today’s engineering problems. Krieg has a strong interest in climate change, a passion for sustainability and wants to research how the environmental impacts of large buildings can be reduced.

Krieg is the 2025 recipient of the Dr. Gordon Springate Sr. Award in Engineering. Named for electrical engineer and educator Dr. Gordon Springate Sr., this donor-funded award is presented annually to a School of Engineering graduate who has demonstrated a material contribution to their community outside of their program.

“I struggled in high school and always felt like I was not the person to succeed in STEM,” she says. “Throughout university, I have found confidence in my passion—using engineering to battle climate change while uplifting the people who need it most. This award will help me boldly pursue that passion.”

Krieg will continue this passion while she works on her doctorate in New Zealand analyzing trade-offs between embodied carbon reductions and earthquake resilience for concrete buildings.

“My interest in climate change mitigation, social equity and their intersection with the built environment drives me to become a structural engineer focusing on sustainable, earthquake-resilient buildings,” she adds. But my experiences as a woman in engineering and a student with a disability inspire me to empower others.”

Heads of Graduating Class

University of BC Medal in Arts: Mihai Covaser

University of BC Medal in Education: tum Marchand

University of BC Medal in Engineering: Conor Manahan

University of BC Medal in Fine Arts: Cady Gau

University of BC Medal in Human Kinetics: Simoné Kruger

University of BC Medal in Management: Shelby Frederick

University of BC Medal in Media: Juan Ablan

University of BC Medal in Nsyilxcn Language: Skye Fay

University of BC Medal in NłeɁkepmx Language: Sunshine O’Donovan

University of BC Medal in Nursing: Mackenzie Themens

University of BC Medal in Science: Zahra Kagda

The post UBCO students shine with top honours at graduation appeared first on UBC's Okanagan News.