Julianne Barry graduated this week with her PhD from UBC Okanagan.

She’s done it all—from undergrad to masters to PhD and research fellow

Julianne Barry is one of those rare breeds of university students. She has spent her entire post-secondary academic career—from those first, nervous fresh-faced days to becoming an accomplished researcher and post-doctoral fellow—at UBC’s Okanagan campus.

Adding to that, each one of her UBC degrees is from a different program, giving her an extensive, yet connected, knowledge base.

“My grandfather had diabetes and many of my grandmother’s siblings died at an early age from heart disease,” says Barry. “Because of my indigenous background, I have always been interested in chronic health issues and how some can be prevented.”

Rewind 12 years and Barry is a brand-new biochemistry student, newly graduated from Keremeos’ Similkameen Secondary School. Four years later she graduates with an honours degree from the Irving K. Barber’s School of Arts and Sciences‘ biochemistry program. She then enters a master’s program in biology, studying heart disease with Associate Professor Sanjoy Ghosh’s laboratory. She recently wrapped up her PhD work with the School of Health and Exercise Sciences, while currently working as a post-doctoral research assistant in UBC Okanagan’s School of Nursing.

“I was chosen to be a research assistant and we are working with Indigenous communities and trying to find a way to blend traditional healthcare practices with western health care practices,” she says. “There are a lot of inequalities and gaps in health care when we’re working with the indigenous communities. We’d like to find a way to close those gaps.”

The four-year project, working with Associate Professor of Nursing Donna Kurtz, will look at issues such as diabetes and obesity in Indigenous populations with six communities in towns like Kelowna, Vernon, Kamloops, Lillooet and Williams Lake.

“The Canadian Institutes of Health Research has funded four areas for chronic disease with obesity and diabetes being one. Our focus has been on asking what are the needs and priorities of your community and can how we bring traditional practices and western programs and services together,” she says. “It’s a locally-driven project and we are hoping to implement their ideas.”

Barry has strong Aboriginal roots with Ontario’s Manitoulin Island and speaks fondly of her grandparents. Many of Barry’s family suffered from heart disease and died at an early age due to the illness. Unfortunately, as she worked on her PhD, both grandparents passed away within a short timespan.

“My grandmother was the core of my family and she passed away a week before my thesis defense. It was a pretty challenging time.”

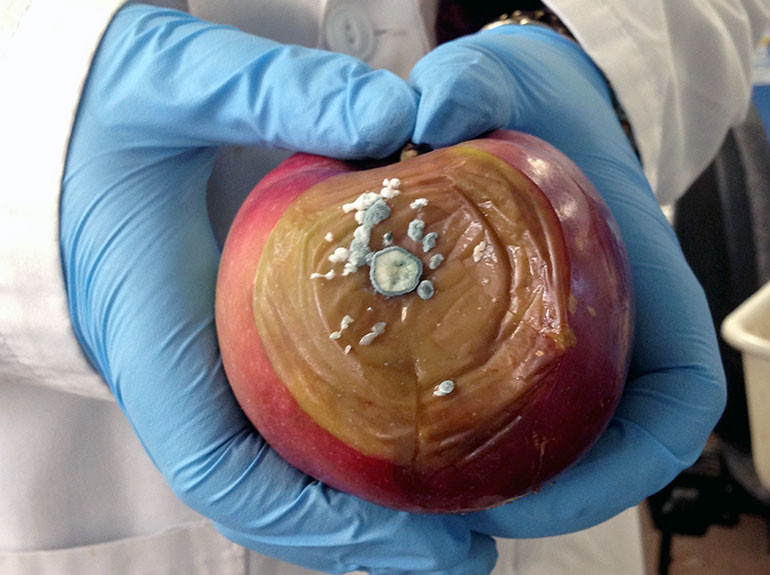

Barry is well versed in diabetes research. Her PhD research was focused on the topic. “Julianne is a rare talent,” says Associate Professor Jonathan Little whose work focuses on health, exercise and diet in the context of Type 2 diabetes. “She continues to expand her repertoire as a postdoc and is truly an example of an accomplished interdisciplinary researcher.”

Little explains how her PhD research spanned from “molecule to human.” It included studies examining how immune cells function in people with Type 2 diabetes at one end of the spectrum to understanding how different types of exercise impact cardiovascular and metabolic function across a 12-month clinical trial at the other. “We looked at the impact of Type 2 diabetes, obesity and exercise on inflammation using the Small Steps for Big Changes program,” she says. “And we followed up with the people a year later and it was fantastic to see the changes these people made throughout the year. These people were overweight or obese and they made significant health changes through the program.”

There was also good with the bad, and Barry notes she was also able to take time away from academia when she and her husband welcomed a baby girl into their family. Now 18 months later and with a toddler who may one day be dependent on her research, she is more determined than ever to continue working to improve health opportunities for all Indigenous people in Canada.

“I feel like my diverse background will benefit my future research and push me to think outside the box.”

About UBC’s Okanagan campus

UBC’s Okanagan campus is an innovative hub for research and learning in the heart of British Columbia’s stunning Okanagan Valley. Ranked among the top 20 public universities in the world, UBC is home to bold thinking and discoveries that make a difference. Established in 2005, the Okanagan campus combines a globally recognized UBC education with a tight-knit and entrepreneurial community that welcomes students and faculty from around the world. For more visit ok.ubc.ca.

The post Newly minted PhD graduate keeps her ties to UBC Okanagan appeared first on UBC's Okanagan News.